Have you

ever spent hours on government websites looking for health information or their

policies and procedures, or simply left out of frustration? Have you ever gone to a clinical trial search

engine site trying to find experimental drugs and therapies to try, or compare

the different options but felt overwhelmed?

You’re not alone. Clearly, most

clinical trial search engines are not patient-focused. Yet when we ask our healthcare providers for more

information on clinical trials, they always point us to the search

engines. The problem is that these

clinical trial search engines are not written or designed with health literacy

in mind.

Health

literacy is the ability to access, understand, and use health information to

make decisions. It doesn’t necessarily

have to do with someone’s ability to read or their education, but whether or

not health information is relatively easy to find, accessible to those with

visual or hearing impairments or other disabilities, and written in plain

language. Many government websites have

cluttered website layouts, too small of a font size (10-point), are difficult

to navigate and find the information you need, and are written with lots of

medical and scientific jargon.

Studies have

shown that health literacy is linked to increased emergency room visits and

hospitalizations, people being able to correctly take their medications, people

following up on medical appointments, being an active participant in their

health care such as self-care and preventive health screenings, and participation

in clinical trials. It’s no wonder, when

you consider how the common clinical trial search engine is designed and its

content. They may be sufficient for a

doctor or clinical researcher, but are far from helpful for the person with an

actual disease or condition or their caregivers. The search engines seemingly rely on the fact

that your doctor or a different health care professional will help the patient

and their family access the information on the clinical trials sites.

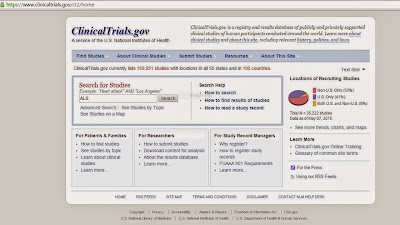

One such

example is www.clinicaltrials.gov. Over the years, this National Institutes of

Health administered site has improved with the addition of a table showing you

the course of action for those assigned to the treatment group versus placebo

or control group. However a lot of the

information is written in medical and scientific jargon. In fact they have to devote a separate page

on their website to define these terms.

Not really a health literacy best practice. Several of the search engine hits list

outcome measures, which is typically of interest to the researcher or treating

doctor but not the patient. Navigating

the various trials can also be challenging.

The study titles they use are overwhelming and not all completed studies

post their results or publications. A

recent study by Utami et al (2014) shows how consumers or patients have trouble

navigating clinical trial search engines and what content and layout would be

best suited for a patient or consumer centered search engine.

In 2007,

Senators Norm Coleman (R-MN) and Tom Harkin (D-IA) introduced a bill known as

the Health Literacy Act, which would

have provided critical funding to expand health literacy research and best

practices and developed federal and state-based patient centered resource

centers. The bill, S2424 had bipartisan

support, was co-sponsored by Susan Collins (R-ME) and Amy Klobuchar (D-MN), and

had support or endorsement from organizations such as AARP, U.S. Chamber of

Commerce, America’s Health Insurance Plans (AHIP), National Health Council,

Institute of Medicine (IOM) Roundtable of Health Literacy, American Medical

Association (AMA), Institute for Healthcare Advancement (IHA), etc. Unfortunately it stalled in Senate and never

was passed.

In 2010 three major initiatives were

put in place to try to address health literacy.

It was a major step forward but did not have the major funding and

widespread impact that the Health Literacy Act would have delivered towards

improved consumer health information.

1. The Affordable Care Act directly and indirectly addressed health literacy by

incorporating health literacy into professional training (section 5301) and

streamlined procedures for enrollment into Medicaid, the Children’s Health

Insurance Program, and the state-based insurance exchanges (section 1413) (Koh

et al, 2012).

2. National Action Plan to Improve Health Literacy, unifies health literacy goals and strategies

for the country and is based on the following two principles: a. All people have the right to health

information that helps them make informed decisions and b. Health services

should be delivered in ways that are understandable and lead to health,

longevity, and good quality of life (Koh et al, 2012).

3. Plain Language Writing Act of 2010 (PL 111-274): Purpose of this Act is to improve

the effectiveness and accountability of Federal agencies to the public by promoting clear Government communication that the

public can understand and use.

Predating

these efforts was a 1998 Amendment to the

Rehabilitation Act, which requires federal agencies to make electronic and

information technology accessible to people with disabilities. Known simply as Accessibility or Section 508

Compliance, everyone must be able to view online information including documents,

websites, and videos regardless of their disability. Web Content Accessibility Guidelines were

established that enables content on the Web to be accessible to a wider range

of people with disabilities, including blindness and low vision, deafness and

hearing loss, learning disabilities, cognitive limitations, limited movement,

speech disabilities, photosensitivity and combinations of these. Some examples of how this is implemented

include video captions and web materials that are compatible with assistive

technologies such as screen-readers.

Although this had been in law for over a decade, it had not been

implemented to its full extent resulting in lawsuits.

So what needs to happen? People with ALS, their caregivers, and advocates need to

demand that clinical trial search engines be health literate. They need to implement consumer or

patient-focused website design, plain language, numeracy, and accessibility

standards. Clinicaltrials.gov is one of

the major search engines, so let’s start there. Ask policymakers to reintroduce

the National Health Literacy Act to provide real funding towards revamping

ClinicalTrials.gov and making other health information accessible.

References

Koh HK;

Berwick DM; Clancy CM; Bauer C; Brach C; Harris LM; Zerhusen EG (2012). New Federal Policy Initiatives to Boost

Health Literacy Can Help the Nation Move Beyond The Cycle of Costly ‘Crisis

Care.’

Senator Norm

Coleman’s Office. Coleman, Harkin

Introduce National Health Literacy Act. [Press

Release], December 6, 2007. Washington,

DC. http://votesmart.org/public-statement/309745/coleman-harkin-introduce-national-health-literacy-act#.VU5LDiFViko

Utami D,

Bickmore TW, Barry B, Paasche-Orlow MK (2014).

Health Literacy and Usability of Clinical Trial Search Engines. Journal of Health Communication:

International Perspectives, 19: sup2, 190-204.

No comments:

Post a Comment